In my previous post, I discussed the very active field of scientific studies of religious behavior and belief, which is currently producing an amazing array of new insights and discoveries. (See the sizable bibliography that I have compiled). At least on the surface, these seem to offer a comprehensive explanation of why people are religious, and in a very deterministic and materialist way. At the least, those arguments supply atheist and anti-religious activists with some powerful arguments, which believers really need to understand. So is there no space left for faith? As I’ll suggest, the counter-arguments are easily found.

Last time, I described the insights of evolutionary theory and the Cognitive Science of Religion, which suggests that human religious responses are deeply rooted in universal human characteristics. As I summarized,

Being human makes us naturally understand things in religious ways, even if we reject any formal or institutional religious affiliation. We are conditioned to look for things that we understand as holy, to project holiness onto particular people or places, to feel awe in their presence, to deny the reality of barriers separating life and death, and we will continue to do so even if all existing creeds have evaporated. Magic, animism, and anthropomorphism are all deeply grounded in our minds, whatever our cultural background. We need the holy, however we imagine it.

If that is true, does that not make us see religion – all religion – just as a culturally adapted response to these simple biological needs? In that perspective, humanity created God according to its evolutionary framing.

Preparatio Religionis

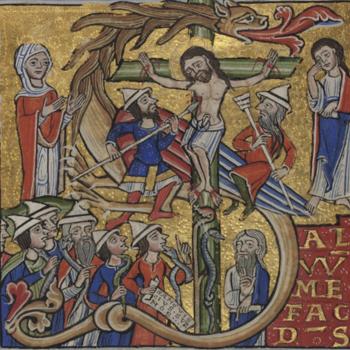

There are various answers to this, which would vary according to one’s own religious tradition, but from a Christian perspective, this is already a very old argument. From early times, Christians looked at pagan religions and found there many themes that seemed very familiar to them. Shrill debates followed about who had appropriated what from whom. Or were these pagan themes a Satanic parody of Christian truth? But over time, a more considered response suggested the idea of the Praeparatio Evangelica, the preparation for the gospel, namely that God had sown seeds of truth in many different ideas and cultures, which would only come to true fruition in the light of Christianity. (Eusebius’s work with that title had an enormous influence on all later apologetics). As a bonus, the praeparatio argument made nonsense of claims that Christianity was some new-fangled cult that had sprung out of nowhere in very recent history, in the days of Pontius Pilate: at least in seed form, it had existed as long as cultures and societies had existed, with their religious speculations.

That idea had a new relevance when later generations of missionaries encountered other world religions, and found them too equally saturated with beliefs and behaviors that looked very familiar to Christians. What a splendid job God had done of preparing the soil for the Christianity that would arrive centuries or even millennia down the road! Indeed, it was a kind of pre-evangelization. The idea found scriptural warrant in texts such as Acts 17, with Paul’s appeal to an unknown God, whom he had now come to expound in the fullness of truth.

Now think of Creation, and assume a God who plans a world in which human beings will recognize the holy, and will acknowledge and worship him. God equips those human beings with the abilities and qualities that they will need to fulfill that task, including hands to pray and feet to be used in pilgrimage or processions. And just as essential for accomplishing that primeval purpose, we are equipped with the awareness of holiness and the accompanying sense of awe, and the other “natural” qualities about which I have been writing. All were built into humanity at that prolonged moment of Creation that we call evolution, which is divinely planned and shaped. When modern scholars find those evolutionary and cognitive features that I have mentioned, they are just discovering the inbuilt mechanisms for faith, which were planned long before the rise of societies and cultures.

Christians have talked of a preparation for the gospel, but this is still more fundamental – a preparation for religion itself, Preparatio Religionis.

The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation

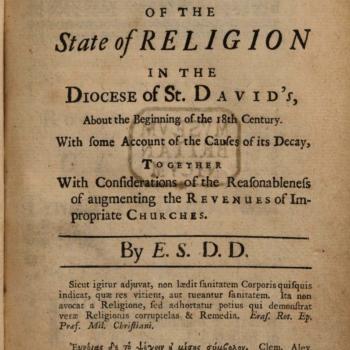

Let me suggest another approach, which is a corollary of that praeparatio argument. During the Enlightenment, and specifically its British manifestations, scientists who were faithful Christians viewed their researches as a form of near-worship. As I wrote here in a post some years ago, they were in quest for the underlying laws that God had left scattered at so many points throughout his Creation. The central idea is summarized in the title of the much-quoted work by pioneering English naturalist John Ray, who in 1691 glorified The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation. Like so many before and after him, Ray was grounding his scientific work in a Wisdom that was a primary theme in Christian thought. For centuries, the world’s greatest Christian church was Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia, which commemorated not a “Saint Sophia,” but the creative Holy Wisdom through which the world was made, and by which it was sustained.

Yes, God demands faith, but He has also left tokens of His Wisdom throughout Creation, and has granted His creatures the intelligence and the desire to seek them and make them known, both for his glory and for the benefit of mankind. When scientists uncover the mechanisms by which that Creation works, they are not exposing the emptiness of religion and its Creator myth – “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!” – but rather they are gaining understanding of the essential systems that God established eons ago.

That idea was later developed in the Bridgewater Treatises. In 1829, the Earl of Bridgewater left a will devoting funds to support the publication of essays “On the Power, Wisdom and Goodness of God as manifested in the Creation.” A series of treatises appeared over the following decade, authored by some of the greatest minds of a dazzling age of scientific creativity. Arguably the greatest contributor was Charles Babbage (1791-1871), a polymath who carved out areas of expertise in mathematics, economics, statistics, and astronomy, and whose Difference Engine foreshadowed modern computing. Babbage used his phenomenal intellect not merely to justify the supernatural and miraculous element in Creation, but to explain why this was a necessary element of that whole structure (I explain this in more detail here). In fact, said Babbage,

it is more consistent with the attributes of the Deity to look upon miracles not as deviations from the laws assigned by the Almighty for the government of matter and of mind; but as the exact fulfilment of much more extensive laws than those we suppose to exist.

All that prevented us from understanding his fact was our lack of “acuter senses and higher reasoning faculties.”

As our science improves, we gain a much better understanding of just how and why the human mind is so strongly predisposed to acknowledge divinities and demons, but that neither justifies nor permits a simple reduction to “That’s all there is. Nothing to see here.” We might just as well ask that if indeed there really was a Creator deity, how else might he have made a humanity that was properly prepared to acknowledge both the material and spiritual dimensions of the universe? If a time traveler had permitted Ray or Babbage to glimpse the cognitive and evolutionary science of religion as it exists in the 2020s, they would have been delighted to witness yet another magnificent example of the practical manifestations of divine wisdom.

Modern scientific theories of religion describe the How. Babbage and Ray supplied the Why. The two parts are complementary.

I am certainly not saying that these are the only possible faith-based responses to those current scientific theories of religion, but either one seems powerful. And I am sure readers will disagree with me at many points.

More next time.