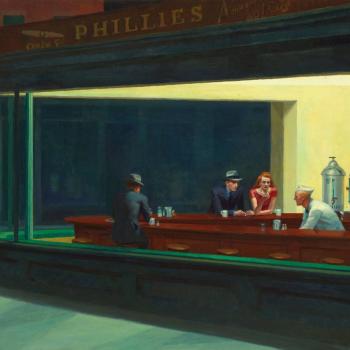

Ernest Hemingway’s short story, “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” is littered with the horrors of loneliness, like a slow-burn thriller but without the catharsis of a powerful conclusion. The aches of loneliness and existential desperation are revealed subtly—almost brutal in their subtlety.

A brief recap of one of Hemingway’s most famous and analyzed short stories: a wealthy old man frequents a bar, drinking alone nightly to combat his despair over the nothingness he sees in his existence. As two waiters, one younger and one older, wait out the old man’s nightly ritual to close the bar, they converse plainly about his state of affairs. According to the young waiter, he has money; therefore, he has no need to despair let alone commit suicide, which he attempted the week prior. The young waiter grows impatient with this “nasty old man” and his non-problem, as he is eager to close the bar and go home to his wife. The older waiter recognizes the symptoms of a despair of nothingness and has a certain understanding of what the old man is doing. There is a certain need for a clean, well-lighted place to go to. The older waiter is willing to keep the cafe open, knowing the need for something to combat the nothingness and darkness that can otherwise swallow a man into itself. Soon, the older waiter will close up the bar and head off to his own place, a bodega nearby, to keep the nothingness at bay until daybreak when he can sleep.

What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada […] Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee. He smiled and stood before a bar with a shining steam pressure coffee machine […] He disliked bars and bodegas. A clean, well-lighted cafe was a very different thing. Now, without thinking further, he would go home to his room. He would lie in the bed and finally, with daylight, he would go to sleep. After all, he said to himself, it is probably only insomnia. Many must have it.

In classic Hemingway fashion, the story is laid bare and there is room to wrestle with what is there. There is evidence that Hemingway’s conversion to Catholicism at a young age was not purely for marriage, as Fordham professor Angela Alaimo O’Donnell highlights some of Hemingway’s Catholic identity in her article, “Hemingway’s Dark Night of the Soul.” In fact, there is plenty to say he practiced to some degree, though he struggled mightily and even called himself “a very dumb Catholic” in a letter to his parish priest. The parody prayers of the older waiter that conclude the story let this struggle spill out into the world, and provoke us to answer for ourselves: do we exist in a vast nothingness or an eternal Something?

Nothingness or Sign?

If out there is only nothingness, then what is this desire that wants a profound something? One that neither the believer nor the non-believer can extinguish entirely, but at best can only subdue with a clean, well-lighted place? In the poem, “Evening Land (Aftonland),” Swedish Nobel-winning writer Pär Lagerkvist examines another side of this despair of nothingness:

My friend is a stranger, someone I do not know.

A stranger far far away.

For his sake my heart is full of disquiet

because he is not with me

Because, perhaps, after all he does not exist.

Who are you who so fill my heart with your absence?

Who fill the entire world with your absence?

You who existed before the mountains and the clouds,

before the sea and the winds.

You whose beginning is before the beginning of all things,

and whose joy and sorrow are older than the stars.

You who from eternity have wandered among the stars of the Milky Way

and through the great darknesses between them.

You who were alone before loneliness,

and whose heart was full of disquiet before any human heart do not forget me […]

The despair of nothingness is in fact evidence of something. The absence of water produces thirst. The absence of food produces hunger. The unquenchable longing for truth, justice, beauty, unity, and love produces despair. Why is there some correspondence to everything but the longing for God? Again, examining the theme of desire as possible evidence, Lagerkvist poses:

[…] If you believe in god and no god exists

then your belief is an even greater wonder

Then it is really something inconceivably great.

Why should a being lie down there in the darkness crying to

someone who does not exist?

Why should that be?

There is no one who hears when someone cries in the darkness.

But why does that cry exist?

The Reality of Despair

Any psychological or biological reasons that attempt to dismiss this cry falls inadequate, in the same sense that nothing fully explains why there is something rather than nothing. Especially in matters of the heart–longing, desire, satisfaction. To live with the assumption that fulfillment of these things is not possible is despair. Philip Larkin also has us look at the despair of nothingness in his poem, “Aubade”:

[…] But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round […]

A brutally honest depiction of the reality of despair being this: “no sight, no sound/No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with/Nothing to love or link with/The anaesthetic from which none come round.” This is a strikingly honest and poetic perspective of existence as the atheist sees it. Most people are scared to talk this way. Others are embarrassed to say the word “heaven.” So rarely, it seems, do we discuss, or perhaps, even let ourselves think about death. “Religion used to try.” Does it still? Is memento mori insulting to the modern man?

Who are you that fill my heart with your absence?

It seems that the child is all too ready to ask and hear about heaven and hell. The adult grows more cautious in such discussions. Even among professed Catholics, talk about heaven seems a little rare for what an astounding promise it is. Certainly, there are many reasons this might be the case, as what can one really say right now? For of course, “What eye has not seen, and ear has not heard, and what has not entered the human heart, what God has prepared for those who love him” (1 Cor. 2:9). And rightly so, we have not arrived. We are on our journey, conforming, converting, becoming. However, by no means is the Catholic immune from the despair of nothingness. It is easy to slip from the silence of God to the dread of nothingness, or back into the noise of modern existence, with just enough distractions to keep one from parking himself in front of that question: Who are you that fill my heart with your absence?

Note: This post originally appeared in full in Solid Food Press Literary Journal (Oct. 23, 2023).