If you missed the setup, it’s pretty important, so I advise going back and reading it.

Why Q?

First of all, there’s no reason to postulate Q in the first place.

If I’m brought up on some important fact I missed about this,

I will of course edit the above remark. (The image stays.)

This is not to say that there wasn’t a body of sayings of Jesus that were recognized as genuine, and from which Christian authors both orthodox and heretical alike drew material. On the contrary, there certainly was. The similarities not only in content but even in wording among the Gospels indicate that much. However, it makes far more sense to propose this original corpus of sayings as an oral tradition, not a written one.

Think about a book as a physical object; pick up the nearest one to you. How long would it take you to copy that book out by hand? (I guarantee you it’s longer than your first guess.) Now imagine you live in classical antiquity. There are no printing presses; if you want a book, you either have to make it yourself or get someone else to. Even making a short book of a few dozen pages1 is going to take weeks, and that’s if you don’t make a ghastly mistake in some physically crucial part of the volume. Remember, even erasers and white-out would have represented a paradise of ease to the classical or medieval scribe, let alone a word processor. Suppose that, fifty-seven pages into hand-copying your little book of five dozen pages, you realize you forgot a whole line of text at the top of the second page. You don’t just have to recopy page two. You almost certainly have to redo everything you have done thus far, as if from scratch, and you’ll need fresh parchment and ink to do it with; and those things only grow on trees in the most literal sense, not the convenient one. All this effort nets you a book: an object that is somehow vulnerable to both fire and water, as well as highly vulnerable to theft … during a period when “scribe” and “professional academic” were just about synonyms because most people can’t read.

Preserving literature orally, on the other hand, was the human default for thousands of years (it’s still done in some places—by everyone on a small scale: urban legends, proverbs, nursery rhymes, etc). Teaching people to memorize things requires no equipment, not even a classroom, and is so easy people occasionally do it by accident. In short, it makes far less sense to propose a document for which we have no real evidence, than it does to accept the actual report of the primitive Church that they continued steadfastly in the apostles’ doctrine and fellowship, and in breaking of bread, and in prayers, and that it was from this set of oral sources, especially the “doctrine” and “prayers,” that the Gospels later derived.

Of course, you could certainly call that oral tradition “Q,” if you liked. It’s a free country.

The Nature of Artifacts

[Editor’s note: this next section isn’t kind about New Testament scholars as a class, or two of them (now deceased) in particular. My detachment probably fails me in this field more than any other; I hope and think I haven’t slid into the trap of “dislike disguised as argument,” but if I have done that anywhere, it’s probably here.]

The whole business of Q illustrates a skewed mindset that seems to emerge over and over in the history of Biblical studies. I’ve found it difficult to put this mindset into words clearly and concisely; let me try hitting it point by point.

To begin with, academics show a tendency to derive documents from older documents and from nothing else. If, say, Mark and Luke both describe the north gate of Jerusalem as being adorned with a golden eagle, it must be because one was reading the other’s work: it can’t be because the north gate of Jerusalem was adorned with a golden eagle and they both, at some point, noticed. Writers like Bultmann and Spong give me the impression of thinking manuscripts reproduce by mitosis, without human involvement—the one type of virgin birth they’d allow, I suppose.2 Guys, listen: I know the postmodern intertextuality bit in Eco’s postscript to The Name of the Rose was fun. But books don’t literally talk to each other. That was just a metaphor.

This resistance to the baffling concept of “people writing facts” seems like it’s of a piece with their approach to authorial intent. Every author has assumptions and biases is a favorite sentiment; which is, of course, quite true. But I can’t help notice that the possibility of modern assumptions and biases distorting a modern scholar’s view of the text doesn’t really come up, and certainly doesn’t get dissected (save perhaps in commenting upon other scholars). The fact that academia has fads and fashions like any other institution, for example—ripe for honest discussion!

Respect My Prioritay

The fact that Mark is the shortest Gospel, for instance, is often marshaled as evidence that it must be the earliest (a hypothesis known as Marcan priority). But how does that follow? Shorter things are not necessarily earlier than longer ones. It’s as natural to give an in-depth explanation and then summarize it, as it is to expand a summary into an in-depth explanation. In the ancient world, particularly because bookmaking was so time-consuming and expensive, composing summaries or “epitomes” of other books was a common practice. It also happens to be exactly how St. Augustine describes Mark’s relationship to the Gospel of Matthew.

But then why, a reasonable voice may interpose, would Mark leave out so much material that was available in Matthew? Well, neither evangelist says they mean to be exhaustive. Mark seems to be more interested than Matthew in following the chronology of things in strict sequence, but neither seems to be aiming at full documentation of Jesus’ life; Mark doesn’t even discuss his birth. The traditional explanation—that St. Peter was the ultimate “source” of Mark, and that he left things out if he had not seen them, because he was giving his personal recollections—seems perfectly economical to me. I will venture to point out that, strictly speaking, assuming a tradition is true or an author is being honest is usually in better accord with Ockham’s razor than the “more rational” genealogies scholars love to concoct. And anyway, this question works against Marcan priority too, because if Mark was a source for Matthew and the author of Matthew was deliberately expanding on Mark’s material, it is even less explicable that Matthew should leave out material that is found in Mark.

The Evolution of an Illusion

Or again: it does make sense to assume Mark must have been first, if you picture Christianity as gradually taking shape over the course of the first century, though “it makes sense” is not quite the same thing as “evidence.” But then, where are we getting the assumption that Christianity took shape gradually over the century in the first place?

A fourteenth-century Russian ikon,

The Synaxis of the Twelve Apostles

The traditional orthodox account was that the Apostles left behind a recognizable, explicit “deposit of faith” with their successors in metropolitan centers from Italy to India. This came with the corollary that heretics were not simply those who developed a previously undifferentiated idea in a direction the majority didn’t like or found threatening, but that they were instead defectors from a known idea that already existed.

Now, there absolutely is a cartoon version of this narrative that does not merit a scholarly hearing. You know, or more probably have read, the sort of thing—people claiming, never with a source, that it’s “Church teaching” Jesus said the first Mass in Latin (no) and spent the forty days between the Resurrection and the Ascension explaining to the Apostles about things like vincible versus invincible ignorance and the distinctions among the Minor Orders (heck no at all). As amusing as it might be to try and maintain that thesis, the people who genuinely believe it generally seem insufferable, and I wouldn’t be able to stay in character. So no, I’m not saying there was no development in the Church’s form or function during the first couple of centuries. There was. We’d know that from the Quartodeciman dispute alone, to say nothing of the disputes and developments recorded in New Testament.

But there is also a version of the conventionally-orthodox narrative that, in my opinion, is worth taking seriously. Listening to some Biblical scholars—at least as reported in media, which, to be fair, I’m sure is very largely the media’s fault, not the scholars’. Anyway. Listening to some of them, you’d think we had no information about Christianity in the first century, except maybe the results of a two-thousand-year-long game of telephone.4 Based on the facts we actually do possess, which principally means the New Testament and the earliest of the Church Fathers, I’m bold to suggest that the development was not nearly so dramatic as either the popular narrative or current scholarly fashion implies.

Dear, I Worry Sometimes About Our Little Darling Academe

I think this partly because the way Biblical scholars interpret the evidence at their disposal, both textual and archæological, often strikes me either as question-begging or just plain silly. For instance, much hay has been made over discoveries of pottery showing images plainly labeled “YHWH and his Asherah,” dating to the monarchic period (i.e., roughly and uncertainly, the eleventh to seventh centuries BCE). This is widely held to be evidence against the historicity of much of the Hebrew Bible.

This baffles me. Any untutored fool might read the Hebrew Bible and think its authors considered it extremely important to only worship one God, because that is what it says in the book. So far so good. However, it would appear that these scholars contrived to come away from the books in question with a second, unrelated impression—namely, that its authors thought their ancestors had mostly done that. This, the book does not say. In fact, it flatly contradicts this. Repeatedly! On the Bible’s showing, foreign cults were already being introduced by the last few years of Solomon’s reign, and less than half the twenty subsequent monarchs of Judah are listed as upholding monotheist orthodoxy. A sizable part of the Torah, most of the Former Prophets (basically Joshua to II Kings) as well as the Latter (basically Isaiah to Malachi), and further chunks still of the Writings,5 are dedicated overwhelmingly to the message All this idolatry my chosen people are so enthusiastically and in fact doing is not very cash money of them.

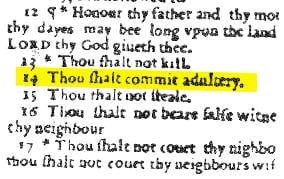

People commit adultery all the time; therefore,

the obvious deduction is that the Wicked Bible

had the original text of this commandment,

and was suppressed due to the uhh

criterion of embarrassment

Now, I don’t even think we need to interpret the Hebrew Bible with a flat-footed literalism. But picture a hardened fundamentalist, who does. For some reason, he is working on an excavation of an undated settlement outside Jerusalem; true to form, the site turns up a shard of pottery with two figures skritched on it, plainly labeled “YHWH and his Asherah.” Do you really suppose (O scholar) that his faith would be shaken? Because, checking said faith against the text that defines it, it would have no reason to be. If his thoughts were as muddled as yours, maybe he’d obligingly be shaken anyway; but I’d anticipate him saying something more like: “Well, this could be from almost any time between the Exodus and the Second Temple. Let’s hope something else is down here that’ll give us a more specific range than that.”

In other words, having gotten the power to read educated into them in first grade, these scholars seem like they finished last grade by getting it educated back out of them again. Biblical studies isn’t the only discipline you see this sort of thing in; history and all the soft sciences (every discipline whose principal focus is researching people we can’t get to know—funny, that) share the same weakness. Regardless, it leaves me with a distinct wariness of trusting their interpretive judgment!

What Happened to Beta Through Psi

But let’s return to that presumption in favor of evolutionary development, which seems almost like an addiction in history as a discipline. The medievals tended to make the opposite presumption (when they raised the question at all): that everything was in a process of continual decay, not to say decadence; that fit comfortably with the general medieval view of things. The evolutionary presumption fits comfortably with the general modern view of things. But the psychological force of either presumption is entirely the force of habit. I expect that that is hard to believe; that is the force habit possesses! So let’s take an example.

From one point of view, it’s true to say that the alphabet we use “evolved” from the Phoenician script. The intermediate forms are clearly traceable—or rather, still in use, in the case of the Greek alphabet. But it’s equally true to say that the alphabet didn’t evolve at all. The alphabet just sat there. What changed was the decisions made by human beings about how they would use the alphabet. Yes, some of these decisions survived and others did not, which sounds like natural selection. But remember, “survived” here is both a metaphor (letters are not alive) and a shorthand. What literally happened is, enough human beings agreed to make the same decision that that decision assumed the social status we call “normal,” which may be defined as “things most people consider it okay to make assumptions about without checking.” We describe this millennia-long process of decisions and incremental changes back and forth as the evolution of the alphabet; and this is not because it has an inherent similarity with the biological distinction between the bonobo and the Bostonian, but because we’re only looking at the letters and not the thing that really changed: human behavior.

Lest I be misunderstood here, the problem with this is not that it’s somehow impious. Piety doesn’t enter into the question one way or the other. Whether such-and-such a form of the letter sigma was in use before 200 CE, or whether Rabbi So-and-so outlived the Emperor Caracalla—these are not the kinds of questions that piety befits a person to answer. They are questions for the historian to investigate, using historical tools: i.e., archæological traces and surviving testimony. And testimony is of greater or lesser strength based on the ordinary criteria of credibility: namely, the intent of the witness; general reliability; and corroboration (direct or indirect) from other sources.

I realized while writing this that I need to include another lengthy digression, this one on the truth-myth-fact distinction. And, as so often, this is already ridiculously long! It’s obviously gotten foolish on my part to say the next one will reach the conclusion (come on, I just need one more blog post man, just one more I swear). But tune in next time for “some more”!

A sycamore fig, one of a few species of fig tree

that grow in the eastern Mediterranean

1If you’re wondering why I say “pages” even though they used scrolls back then, (a) “Yes, you’re very smart. Shut up.”, (b) pages kind of existed in scrolls, in the form of columns of text side by side, as in the photos for this article, and (c) we’re going to mostly ignore the difference between scrolls and codices (or codexes—codex is a correct singular for both, and codices can also take codice) in this post. But as long as we’re here! Codices are a much later invention, dating to the third century BC; it took them a few hundred years for to replace scrolls. I’m not familiar with all the reasons for this, but I imagine at least two played a role. First, codices are slightly more involved to make than scrolls (e.g., you have to bind a codice, i.e. sewing the pages together at the spine); and second, scrolls were traditional, which probably gave them caché. There was also an interesting rivalry between Alexandria, whose library represented the scholarly gold standard throughout the Mediterranean, and Pergamon, where the codex was invented. (I possess no information on whether the Egyptians, jealous the Pergamenes thought of it first, ran a publicity campaign with the slogan Codices Are Fake And Gay: Read A Scroll The Manly Way!, so I’m forced to assume that they did until evidence turns up to the contrary.)

2If you haven’t heard of them till now, allow me to ruin your day. Rudolf Bultmann was an existentialist Lutheran theologian who argued for “demythologizing” the New Testament, and that what was important about Jesus was that he preached and was crucified, not the specific quality of his life or teaching. As Dorothy Sayers drily observed in 1947, “The only drawback to this … is the practical difficulty of arousing any sort of enthusiasm for the worship of nothing in particular.” (I’ll give him his dues, though: Bultmann was a staunch, public critic of the Nazis, which meant a lot in Germany in the 1930s!)

The late John Shelby Spong was an Episcopal bishop and, for lack of a better word, theologian. I say “for lack of a better word” not because of my utter and undoubted lack of respect for Spong; rather, I sincerely don’t know if that’s the right word for what he was doing. He argued, among other things, that Christianity needed to move away from little things like theism in order to stay relevant (relevant to what, I can’t say). To my mind, a more obvious strategy would have been to move oneself away from Christianity, if one feels that way about its basic premise. I’d find his memory less despicable if he had, out of human decency, desisted from priestly ministry in particular—for of course that is not only exercised but paid for, by parishioners, on the assumption that one believes in many things handily listed in the creeds, God included. As things were, I consider him (if for atypical reasons) to have been exactly the same kind of thief as Jim Bakker or Kenneth Copeland.

3Obviously all Christians were Jews at first, but even in the beginning, some of these were Gentile-born converts to Judaism, also referred to as proselytes. (“Nicholas, a proselyte of Antioch” is mentioned as one of the first deacons in Acts 6.) These should not be confused with the God-fearers [θεοσεβεῖς, theosebeis]. God-fearers were Gentile sympathizers who worshiped the Judaic deity, and observed at least some Jewish practices, but without full conversion. (Conversion involved not only a lengthy period of instruction, second-class status among fellow Jews, and annoyances like keeping kosher, but circumcision—a rite which, undergone as an adult, without modern anæsthetics and in a world where antiseptics were as yet controversial, was both debilitatingly painful and carried a remote chance of losing a bit more than your foreskin.) The “plot” of the first half of Acts shows us the outward spread of Christianity as if through a series of concentric circles, hinted at in the first chapter’s witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judæa and Samaria, and to the uttermost part of the earth. The first disciples are native Jews; then in chapter 6, converts to Judaism are explicitly mentioned; in chapter 8, we get both Samaritans and the remote Jews of Ethiopia (in the eunuch); in chapter 10, we reach God-fearers; somewhere in the course of St. Paul’s second mission—at Philippi or Athens, maybe, though the text is not explicit on this topic—we get the first Gentile Christians with no prior connection to Judaism.

6One day, I will find the person who started this “we only have copies of copies, it’s game of telephone” trope (than which it is not possible to conceive a distortion of how scholarship works more obnoxious, boring, and destructive); and when I do, I will execute the sole curb-stomping I expect my life to include.

5The Hebrew Bible is arranged in three sections. First is the Torah or Law: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Then come the Nevi’im or Prophets, divided into two categories: the Former Prophets are Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings; the Latter are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and The Twelve (Hosea to Malachi inclusive). If you’re wondering what happened to a bunch of books from the middle there, they belong among the Ketuvim, the Writings: Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the Five Scrolls (read on set holy days and consisting in the Song of Solomon, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther), Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles. In addition to the order, a few divisions are different—Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles all remain undivided, while The Twelve and Ezra and Nehemiah are amalgamated. The initials of the three sections, Torah–Nevi’im–Ketuvim, are where the Hebrew Bible gets its other name, the Tanakh.

The standard Christian ordering of the books is inherited from the Septuagint. That is also where we get the “extra” books of the Catholic canon, as well as their traditional placements: Tobit and Judith (between Nehemiah and Esther), I and II Maccabees (between Esther and Job), Wisdom and Sirach (between the Song of Solomon and Isaiah), and Baruch (between Lamentations and Ezekiel, and including the Letter of Jeremiah as an appendix). I have passed over the additions to Esther and Daniel, on the grounds that my readers can probably guess where these are to be found.