The wall of separation between church and state is in the news again. Recently Rep. Mike Johnson, the new U.S. Speaker of the House, told an interviewer that “separation of church and state” is a “misnomer.” “People misunderstand it,” Johnson said. “Of course, it comes from a phrase that was in a letter that Jefferson wrote. It’s not in the Constitution. And what he was explaining is they did not want the government to encroach upon the church — not that they didn’t want principles of faith to have influence on our public life. It’s exactly the opposite.” Johnson went on to say that the founders believed religion and morality were central to maintaining government. “And that’s why I think we need more of that — not an establishment of any national religion — but we need everybody’s vibrant expression of faith because it’s such an important part of who we are as a nation.”

Neither Jefferson nor any other founder intended religion to be banished from public life. That isn’t what the “wall of separation between church and state” refers to. People are free to bring their religious convictions to the public sphere as much as they like. But Johnson imagines that somehow there can be a one-sided wall that stops government from encroaching on religion but allows religious institutions to encroach on government. The power of government can then be used to encroach on their fellow citizens who may not share their religious views. And while the words “wall of separation between church and state” are not in the Constitution, Jefferson used the phrase as a metaphor to explain the opening phrase of the First Amendment, which very much is in the Constitution. For more background on how Jefferson used the phrase, see “Jefferson’s Wall of Separation Between Church and State.”

Jefferson and the other founders of the nation were primarily concerned about religious factionalism. What might happen if a particular religious faction gained control of Congress and the White House and began to write laws that favored their religion? Or that compelled all Americans to obey laws based on that religion’s beliefs? They knew the history of the wars of religion in Europe, in which armies fought to determine if their government would be Protestant or Catholic. Something like that might happen in the United States. For that reason, the first clause of the Bill of Rights begins, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” “Establishment of religion” refers to designating an official state religion. The authors of the Constitution reasoned that if the federal government didn’t have the power to give one religion special privileges over others, then religious wars wouldn’t break out over which church controlled the government.

Why the Wall of Separation Has Two Sides

In human history, most of the time where there is oppression of religion it is at the hands of another religion. This is why the wall of separation has two sides. It prevents government from encroaching on religion, but it also prevents religious factions from taking over government and using it to enforce their particular religious beliefs (which would end up encroaching on those other religions). A one-sided wall, even a metaphorical one, doesn’t work.

The Constitution itself was deliberately written without mention of God. This was not an oversight but was debated by the Constitutional Convention. Some of the members wanted to say something about God, but they were outvoted. (For more background, see “The Myth of the Christian Nation.”) The provision in Article VI of the Constitution forbidding a religious test as a requirement for office was widely denounced by those opposed to ratification of the Constitution. A New Hampshire critic complained that “according to this [provision] we may have a Papist, a Mohomatan, a Deist, yeah an Atheist at the helm of Government.” Well, yes. We most certainly may. This is what religious freedom looks like.

James Madision, the chief author of the Bill of Rights, had opposed religious laws while he was a member of the Virginia legislature. In a text called “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments” (1785) he wrote that religion must be a matter of individual, personal conscience. It must not be dictated and controlled by the majority opinion of society. The Establishment Clause prevents government from encroaching upon the church, as Speaker Johnson says. But it also prevents government from being used to force the religious beliefs of a majority faction on the minority. Certainly individuals may consider their religious beliefs when forming opinions on public policy. But attempts to use law to encode religion-based policy is overreach. For example, a law that criminalizes homosexuality (which Mike Johnson has said he supports) because God supposedly doesn’t like it would be a breach of the wall of separation. (See “James Madison and Religious Freedom” for more background.)

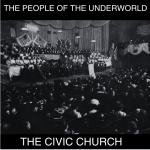

Religion in the Public Sphere

The United States has a rich history of religious activism. The abolitionist movement to end slavery was very much a Christian movement. A clergyman was behind the movement to end child labor. When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King. Jr., worked for racial equality, he was drawing on evangelical tradition. Likewise, when the Rev. William Barber organized the Moral Monday movement, he was drawing on evangelical tradition. These are all examples of religion in the public sphere that have nothing to do with the wall of separation. There are a handful of ordained clergy currently serving in the U.S. Congress, and that doesn’t violate the wall of separation, either. Religious people and institutions have the same rights of free speech as other people and institutions. The Establishment Clause and the wall of separation are limits on what government can do. But that limit protects us from oppression by religious theocrats.

Large religious factions may sincerely believe that some behaviors are sinful and shouldn’t be done, and they are free to say so publicly. But unless there is a secular reason for banning such behavior, government is supposed to leave it alone. “The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others,” Thomas Jefferson wrote. “But it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

The Wall Protects All of Us

Since the founding of the nation there have been those who really want the U.S. to be a Christian theocracy rather than a republic of the people, by the people, and for the people. Speaker Mike Johnson appears to be a Christian theocrat. “Johnson is in fact a believer in scriptural originalism, the view that the Bible is the truth and the sole legitimate source for public policy,” Marci A Hamilton wrote in The Guardian. Johnson believes the founders of the United States intended it to be a “biblical” republic, Hamilton continues. But in fact, the founders were sons of the 18th-century Enlightenment. They celebrated reason and free thinking. Many of them were more Deist than Christian. I cannot say if Mike Johnson knows he is lying about the founders and the Constitution, but he is.

See also “I Read Mike Johnson’s Legal Filings. They Reveal a Distinctive Pattern” by Kimberly Wehle at Politico. As a lawyer, Johnson handled many free speech and religion cases before he was elected to Congress in 2016. Wehle writes that Johnson has been a fervent defender of First Amendment protections, but only for Christians. “When nonreligious secularists brought a religion-based challenge, he took the other side,” Wehle writes. “Johnson’s theory, summed up, appears to be what might be dubbed, ‘the First Amendment for me but not for thee.'”