If you have been a student of witchcraft and Wicca for any length of time, by now you’ve heard a timeworn and banal tale that goes something like this:

Witchcraft was illegal in Britain until 1951, when the Witchcraft Act of 1735 was repealed and replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act. This lifting of the law enabled Gerald Gardner and others –but mainly him — to be more open and birth modern pagan witchcraft into the public awareness.

All of this quotidian trope is sort of true, but only in a more nuanced way than is customarily presented. It’s a good story and it feeds into the Murrayite thesis that a cult of ancient paganism had persisted in Europe, hiding underground until our more enlightened and liberated time. It’s a powerful modern origin myth and goes generally unquestioned, like an early example of a meme. Perhaps it’s high time that we opened up a little about the Witchcraft Act of 1735, commonly and erroneously cited as the last draconian law against pagan witches. Getting into the weeds of this is tricky, and requires some careful consideration. Hopefully, there’s food for thought in what follows…

The first thing you should know about the Witchcraft Act of 1735 is that it repealed and replaced ALL previous medieval laws in England and Scotland against witchcraft. By 1735, prior witch hunts had troubled the enlightened times and what concerned educated, urban law makers and intellectuals most was that belief in witchcraft was rank superstition at best, and plain con-artistry at worse. Famous witch-finders Matthew Hopkins and John Stearne have been accused of profiting from their witch hunting pursuits and subsequent publishing endeavours. Belief in magic and witchcraft had been on something of a decline in towns and cities, replaced with suspicion of fakery and fraudulence, especially where mediumship and fortune telling was implicated — both of which are still covered in U.K. law under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, which in turn replaced and subsumed the 1951 Fraudulent Mediums Act. Furthermore, the horror of witch trials loomed over lawmakers and enlightened thinkers in the cities who were turned away by the manner in which parochial and rustic people could turn on each other and pursue accusations all the way to the gallows. Witch finding was now abhorrent, and the new Act of 1735 would finalise it, being formed fundamentally to prevent accusations and witch hunts. It begins:

“…no Prosecution, Suit, or Proceeding, shall be commenced or carried on against any Person or Persons for Witchcraft, Sorcery, Inchantment, or Conjuration, or for charging another with any such Offence, in any Court whatsoever in Great Britain.”

To restate that: nobody can be tried for witchcraft; a far cry from a law against witchcraft! In this context, the 1735 Act ensured that accusations of witchcraft could not be levelled nor pursued in the way that they had been previously. The witch-hunts were, so it was thought, over but the new Act did, however, proscribe anyone from laying claims to any such powers, making it criminal to

“…pretend to exercise or use any kind of Witchcraft, Sorcery, Inchantment, or Conjuration, or undertake to tell Fortunes, or pretend, from his or her Skill or Knowledge in any occult or crafty Science…”

Where penalties had once included and extended to public execution, the worst one could expect under this new law was a year imprisonment — still not to be sniffed at. The aim of the Act was clear: nobody may accuse another of witchcraft or sorcery nor pursue such claims as previously enacted by earlier laws. Furthermore, nobody should pretend to such powers, particularly for financial gain.

It is in this last part of the 1735 Act that we see the basis of the Fraudulent Mediums Act of 1951, and it’s later subsuming into the trade descriptions legislation of 2008— in short, the law would be now used to prohibit conning people with table tapping and other such nefarious activities. With the 1951 Act, Gerald Gardner was freer than before to say that he was practicing witchcraft — whereas the previous law protected him only from persecution by accusation — it would have been illegal to accuse him!

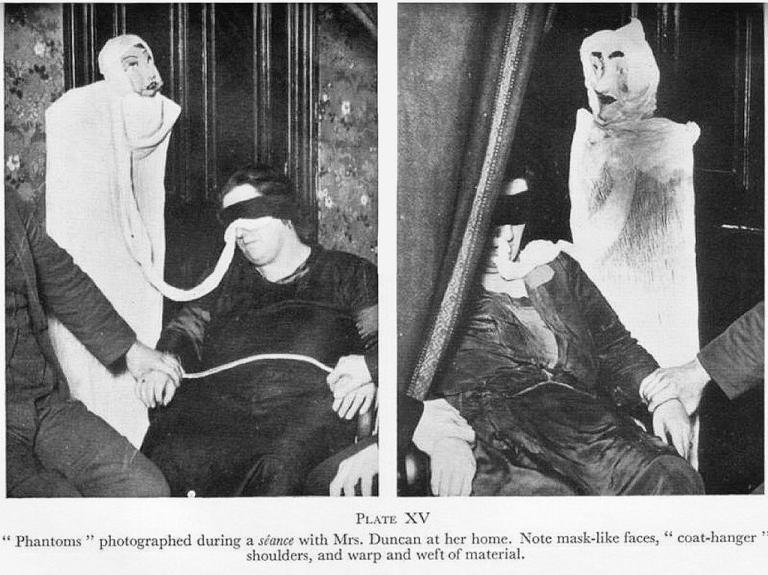

One of the last persons in Britain to succumb to the 1735 Witchcraft Act, prompting a revisit to its arcane legislation, was the materialisation medium Helen Duncan in 1944.

…prominent spiritualist and Labour MP Thomas Brookes, had been campaigning for less heavy-handed policing under the 1735 Act throughout 1943, but Duncan’s arrest in 1944 prompted calls for significant changes to the law. [1]

Whilst Duncan was imprisoned for 9 months under the 1735 Act, it should be noted that her famed ectoplasm producing routine turned out to be cheesecloth when inspected. Duncan agreed to testing her seances with famed psychical researcher Harry Price in 1931, after which he concluded that there was deception used. In 1933, Duncan was arrested and fined £10 after a court deemed her activity fraudulent.

The Labour MP Thomas Brookes lead the campaign to repeal the 1735 Act, arguing that not all mediums were fraudulent as this had been the crux of the case against Duncan, and the meat of the 1735 Act used against her. The Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 made provision for this fact, assessing only those where “it is proved that [they] acted for reward”. This reluctance toward profiting from Spiritualism was underlined by a clause in the 1951 Act which prompted a now oft-repeated caveat used by tarot readers and psychics alike, advising that such services are intended for ‘entertainment purposes only’:

Nothing in subsection (1) of this section shall apply to anything done solely for the purpose of entertainment.

Like most things in life, it’s complicated. It isn’t strictly true that Gardner couldn’t come out with his new pagan witchcraft prior to 1951 — Dion Fortune and Aleister Crowley had been happily publishing about magic a long time prior to the publications of Gardner’s High Magic’s Aid in 1949. Indeed, and importantly, the law of the 1735 Witchcraft Act didn’t prohibit witchcraft at all, rather it didn’t recognise that any such thing existed. The story that Gardner as a witch, and the witchcraft that he spearheaded, couldn’t claim to be a witch prior to 1951 is not quite correct. In reality, the relevant clause of the 1735 Act specifically is written:

…for the more effectual preventing and punishing of any Pretences to such Arts or Powers as are before mentioned, whereby ignorant Persons are frequently deluded and defrauded…

In essence, the Act prohibits defrauding persons, or pretending to occult powers for profit. Of course, lawyers can interpret that several ways, but the basis remains the same and the intention was to restrict those fraudulently telling fortune, finding treasure, summoning recently deceased spirits, etc. The devil is in the detail and, as this quote above indicates, it rests upon the defrauding or deluding — the indication being that there has been an exchange as a result of these claims and that deceit was the modus operandi — there has to be an evidentially harmed other party. This was evinced in Gardner’s lifetime by the story of Helen Duncan, the last person the UK to be imprisoned under the 1735 Act, and who definitely used deception in some of her seances.

All of this isn’t to say that Gerald Gardner didn’t feel the he couldn’t publicise his witchcraft until the repeal of the Witchcraft Act 1735 – he quite possibly did. However, the Witchcraft Act of 1735 was utterly unlike its predecessors. It is also possible that Gardner was riding the wave of publicity surrounding the repeal of the 1735 Act and it was evidently known and on people’s minds, and in the zeitgeist of the burgeoning witchcraft community. Indeed, Doreen Valiente wrote extensively about this subject in her 1989 book The Rebirth of Witchcraft, although focussing heavily upon the trial of Duncan under the Act, and repeating her own feeling that the 1735 Act’s main impact was to demote witchcraft from a capital offence. This despite quoting the politician and Home Secretary Henry Brooke, who stated in Parliamentary session that “witchcraft had ceased to be a criminal offence in 1735”!

“…historian Owen Davies has pointed out that, in fact, the Witchcraft Act strove to eradicate the belief in witchcraft once and for all among educated people…” [2]

During the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s it’s quite possible that knowledge of the law amongst the average populace was actually quite scattered and we have the luxury of being able to access the Act at the click of a mouse. Therefore, an understanding of the Witchcraft Act 1735 might have hinged almost entirely upon the erroneous understanding that, like its predecessors, it legislatively forbade witchcraft, when in actual fact the 1735 Act simply denied it altogether.

That being said, Gerald Gardner was actually quite cognisant of the 1735 Witchcraft Act and it’s intent. In his last book, The Meaning of Witchcraft, Appendix 3, he writes:

“In the reign of George II, the Witchcraft Act of 1735, which said in fact that there was no such thing as witchcraft, and no one in future should be prosecuted for it; but that anyone who pretended to supernormal powers should be prosecuted as an impostor.” [3]

The reality was that, as in the case of Helen Duncan, prosecution only usually occurred under the Act where the ‘pretence’ had involved deception and been for profit. It is possible that Gardner may have been liable under law if he had profited from a book in which he claimed to witchcraft, but there had been no such precedent for such a case. The usual subjects of prosecution were, therefore, mainly targeted Spiritualists and mediums. Simply ‘pretending’ to be a witch would be otherwise mostly legally inoffensive in and of itself, unless there was an actual real terms loss or damage evidentially occurring. Bringing a law suit against somebody because they claimed to be a witch would have been unlikely to be represented in a court of law in Britain at the time, unless there was evidence of harm or loss of moneys as a result of deceit.

The Wikipedia entry for The Meaning of Witchcraft delightfully perpetuates the myth of the 1735 Act in it’s first paragraph, stating that the book was able to be published “…only after the British Parliament repealed the Witchcraft Act of 1735…”. Regardless of the idea that mid-twentieth century occultists might have been trepidatious about publishing such material, it should be remembered that in 1910 MacGregor Mathers filed a lawsuit against Aleister Crowley for publishing Golden Dawn material in his periodical The Equinox. The court found in Crowley’s favour and the trial garnered much publicity – and yet, nobody thought to evoke the Witchcraft Act of 1735 against either men in the case. It goes without saying, of course, that Crowley published the Equinox from 1909, including within its pages considerable material on occultism and magic. He profited from his broader magical efforts, especially dues from OTO membership, and selling charters such as the one he issued to Gerald Gardner in 1947.

Furthermore, Dion Fortune published her first non-fiction literature concerning occultism in 1928 – The Esoteric Orders and their Work – followed by the 1930 companion volume – The Training and Work of an Initiate. The unambiguous title and nature of these books barely disguised the content and intent, and yet never drew accusations under the Witchcraft Act 1735. Indeed, Fortune makes veiled reference to the Witchcraft Act of 1735 in her still popular 1930 work Psychic Self-Defence, which draws from many autobiographical details:

“It is cases such as these which make the honest investigator of occult phenomena thankful that there is upon our statute-book a law which enables magistrates to deal effectively with occultists who prostitute their powers. It is so generally known that no initiate may use the occult arts for gain that it is difficult to sympathise with people who pay some advertising occultists his half-crown or half-guinea and then find themselves let in for unpleasantness.” [4]

Needless to say, this is clear reference that Fortune was not only aware of the 1735 Act, but thankful for it in defending ‘honest’ investigators and initiates of occultism against those who would sell, or ‘prostitute their powers’.

Gardner includes in his opening gambit of The Meaning of Witchcraft, first published in 1959, reference to the repeal of the 1735 Act quite early in chapter one. He calls it the last of the ‘witchcraft acts’ which, while being technically true in title, is a little disingenuous considering that the 1735 Act repealed all such Acts to which he alludes. He does acknowledge that Spiritualists had been prosecuted under the Act, likely thinking of Duncan, but fails to acknowledge that these were not witches, and who were profiting and had been proven to use deception. This is in stark contrast to Fortune, who seems to have been grateful that genuine initiates were divided from those who sought to earn from the Craft and were, therefore, subject to the law “upon our statute-book”. Whilst there is little doubt that Gardner could have faced considerable opposition to his open and frank discussion about witchcraft at the time, it remains questionable whether the Fraudulent Mediums Act was considered “highly obnoxious to certain religious bodies”, and his position hinges on his firmly held determination that witchcraft was a persecuted remnant of pagan religion that was simply misunderstood. It is evident from Gardner’s writing that he deeply despised Christianity at this point, and this coloured his perspective considerably in the pursuit of his pagan witchcraft.

By the close of the 1950s and the release of The Meaning of witchcraft, Gardner had rather over-egged the pudding, and over simplified the reality, which was gleefully pointed out in time by the likes of Robert Cochrane who trod a more considered path. In a 1963 article for Psychic News, Cochrane contributed to the conversation around modern witchcraft, in contrast to Gardner’s simplified neopaganism and anti-Christian rhetoric, explaining:

“Genuine witchcraft is not paganism, though it retrains the memory of ancient faiths. It is a religion mystical in approach and puritanical in attitudes. It is the last real mystery cult to survive, with a very complex and evolved philosophy that has strong affinities with many Christian beliefs.” [5]

Once again, Cochrane seemed conscious of the tension around the Spiritualist movement and the development of witchcraft and occultism in the twentieth century, writing in the same article:

“The Spiritualist asks for ‘miracles’ vide the spirit of another world. The witch, or anyone interested in magic, tries to work those ‘miracles ‘ by herself… It is of course the old controversy between the occultist and the Spiritualist.” [6]

It is worth noting here that Cochrane, ever the controversialist, submitted this article to Psychic News, a weekly British Spiritualist newspaper founded in 1932. Once again, this weekly publication defied the Witchcraft Act of 1735 openly, even writing in support of the materialisation medium Helen Duncan who had been prosecuted under the Act on several occasions. Articles from the world of neopaganism and Wicca were published by Psychic News in the 1950s and ’60s, even printing this piece from Cochrane purporting to be a self-confessed witch who evidently drew a line between Spiritualists and occultism.

Needless to say, the realities are far more complicated than an offhand, over-simplified cliché that has become embedded in the oft-repeated histories of modern witchcraft. As Gardner’s bias saw in the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 an easing of the legislature in terms of religious freedoms, the truth is that it was occasioned with Spiritualist mediums in mind and not a modern pagan cult. None of this suggests that there isn’t still, even today, great danger and harmful reactions toward modern witches, Wiccans, pagans, occultists and esotericists of every kind. We don’t live in a perfect world, and there remains corners of it, both near and far, that persecute others for their beliefs, especially witchcraft.

Furthermore, the old horrors of the medieval European witch-hunts are not relegated to the past, and most modern occurrences take place in sub-Saharan Africa, although we must remember that parts of Asia, South America and Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia are extremely hostile. In these instances, the prevailing cause is projection and fear, economic and social conditions that nurture bigotry and hate, driving people to turn upon themselves and victimise anyone considered different, or ‘othered’.

Post script:

To avoid confusion, and make clear that there is no controversy here, I am not suggesting that there were no witches in the past — on the contrary, there absolutely were! Nor am I asserting that Gerald Gardner and company didn’t feel that the Witchcraft Act 1735 was an impediment to them — they evidently did and said so.

What I am saying is that we live in more informed times and, in the pursuit of the genuine article, we move through a lot of weeds. Given different information, would our forebears have behaved and thought differently? I think that goes without saying. If we are to advance our Craft, it’s history and an understanding of its place in the world today and in the future, we need to have the adult conversations around these issues. By expanding our knowledge around these and associated matters, we don’t “debunk” or “dismiss” them; on the contrary, we make them richer.

The Witch Compass: Working with the Winds in Traditional Witchcraft

The Witch Compass is Ian Chambers’ first book, published in 2022 with Llewellyn, and is available through all good booksellers. Signed copies of The Witch Compass are available from the author’s website: surrey cunning.co.uk

Explore the compass of the eight winds, a magical circle at the heart of Traditional Witchcraft. More than a tool for protection or raising power, this framework provides the ritual means to traverse the worlds and a mythic landscape that can be accessed at any point in time and space. Traditional Witch Ian Chambers teaches how the Witch Compass represents an entire worldview, a cosmological map, and a method for magic and revelation. He helps you develop your own compass and use it for divination, spirit work, and practical sorcery. This book shows you the world through the lens of your Witch Compass and reveals the many realms and spirits available to you.

“With this invaluable book, the aspirant unto traditional Craft and the seasoned practitioner alike are carefully guided through the workings of the compass as the map, via which the Crafter may traverse magical realities, encounter spiritual presences, and commune with ultimate Truth.” – Gemma Gary, author of Traditional Witchcraft, A Cornish Book of Ways.

“A scholarly, inspiring, and eminently informative work. I give it my highest recommendation.” – Lon Milo DuQuette, author of The Magic of Aleister Crowley.

“I found this a most fascinating and informative book, describing as it does the rationale behind the actual working of the compass, with plenty of practical demonstrations and exercises to enable the reader to experience the compass for themselves…This is a sorely needed book that gets to the heart of the inner workings of the compass and provides a wealth of most valuable material for both the beginner and more experienced practitioner alike. I congratulate Ian on producing an approachable and understandable book which will add greatly to the sum of available knowledge on a sometimes obscure and difficult subject.”―Nigel G. Pearson, author of Treading the Mill.

N.B.

The common misconception is that Helen Duncan was the last person in Britain to be prosecuted for being a witch and this is false for two reasons:

1) there remained no laws in Britain against witchcraft in 1944, and

2) I’ve found no suggestion that Duncan was regarded by herself or associates as a witch.

The second misunderstanding, and an alternative of the first, is that Helen Duncan was the last person convicted under the Witchcraft Act 1735. In fact, that honour belongs to Jane Rebecca Yorke who was found guilty in late 1944 under the Act. She received a fine of £5 and was bound over for three years.

With today’s special effects and AI technologies, looking at photographs of Helen Duncan materialising ectoplasmic spirits is not good, and the cheesecloth and papier-mâché wouldn’t fool a child today. Show the pictures to a young adult and see if they believe that they are looking at a spirit made manifest.

Footnotes

[1] https://archives.blog.parliament.uk/2020/10/28/which-witchcraft-act-is-which/ [2] https://amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/jan/24/comment.comment3 [3] Gardner, Gerald Brosseau. “Appendix 3.” Essay. In The Meaning of Witchcraft. (Boston, MA: Weiser Books, 2004), 256. [4] Fortune, Dion, Psychic Self-Defence, (Boston, MA: Weiser Books, 2011), 68. [5] Cochrane, Robert. ‘Genuine Witchcraft Defended’ Psychic News. November5th, 1963. [6] Cochrane, Robert. ‘Genuine Witchcraft Defended’ Psychic News. November

5th, 1963.