The ancient Stoics worked to practice the four “cardinal” virtues (the word “cardinal” coming from the Latin “cardo,” meaning “hinge”). Our lives “hinge” on making the right decisions, and following those four virtues: wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance. These are ancient, time-tested character traits that ensure genuine and lasting happiness if one is able to consistently adhere to their demands. The path of virtue is not an easy one. To help guide you on that path, here are three stories from the ancient world that help to illustrate the virtues, in hopes that when tied to narratives, you may better remember the lessons the virtues wish to impart.

The ancient Stoics worked to practice the four “cardinal” virtues (the word “cardinal” coming from the Latin “cardo,” meaning “hinge”). Our lives “hinge” on making the right decisions, and following those four virtues: wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance. These are ancient, time-tested character traits that ensure genuine and lasting happiness if one is able to consistently adhere to their demands. The path of virtue is not an easy one. To help guide you on that path, here are three stories from the ancient world that help to illustrate the virtues, in hopes that when tied to narratives, you may better remember the lessons the virtues wish to impart.

The first story helps to illustrate the simple choice between virtue and vice, its opposite. To the ancient Stoics, virtue was the only genuine good, vice was the only thing that was genuinely bad, and everything else was simply indifferent (though some “indifferents,” such as wealth and friendship, could be considered to have “preferred” status). We begin the narrative triad with “Hercules at the Crossroads.”

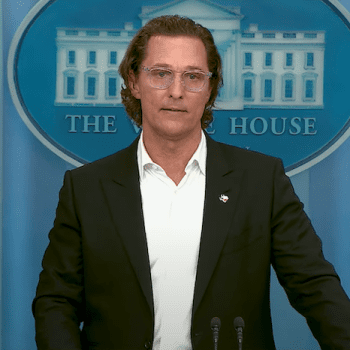

One day, Hercules went for a walk in the wilderness. No one knows where he was headed, or why he was headed there. Before long, he came across a crossroads that offered two possible paths on which to continue his journey. Before he could select one of his own accord, two stunningly beautiful goddesses appeared before him, one on each path. To his left, standing in the center of the road, was Kakia, the goddess of vice. To his right, Arete, the goddess of virtue. Both goddesses beckoned him, each laying out the argument for taking their respective paths. Kakia promised that, if he should select her path, he would enjoy a life of ease and comfort, being able to indulge in every mortal pleasure one could imagine. She did add, as a mumbled caveat, that the pleasures would be fleeting and short lived, but what of that? He would always be able to pursue more once the joy of each wore off. The important thing would be that he would never again face difficulty or challenge, only sensual pleasure and relaxation. Such was the choice Kakia presented to him.

Arete offered him a life of genuine happiness–but it would come at a price; the path to it would be painful and arduous, with challenges around every turn. In the end, the happiness and fulfillment he would achieve would be lasting and genuine, unlike Kakia’s illusory pleasures.

Now, what choice would you make? Perhaps a better exercise is to look back at your life up to this moment and assess which choice you have already made. No doubt you have sought out your share of challenges, and at times indulged in sensual pleasures that did not last, perhaps some you even came to regret pursuing. Many are trapped in worlds of vapid and temporary pleasures, some to the point of addiction, and Kakia keeps them on a short and tight leash. Others avoid the pleasures Kakia’s path offers; if they don’t do so altogether, they are at least able to moderate and control their indulgence in them. They actively seek the more challenging and arduous path, as they can see the difference between lasting happiness and that shadow of happiness which is fleeting. Hercules, after hardly a moment’s consideration, chooses to follow Arete’s path, spurning the goddess of vice and opting for a life of challenge and hardship that will, in the end, provide lasting fulfillment.

The second narrative from the ancient world that can teach us something about virtuous living is the story of Sisyphus. Sisyphus was the King of Ephyra, and a brutal and avaricious king he was. Though he favored and promoted some positive things, such as commerce with other city-states (doubtless because of the wealth such commerce brought him), he was ruthless to those who visited him, wanting to show the world that he was not a sovereign with whom to trifle. Many visitors to his palace lost their lives to his tortures. Treating his countrymen, particularly those who came to him in need of assistance, in such a manner was not only behavior unbecoming a king, but such behavior was not without risk.

The ancient Greek law of hospitality would have you bathe, feed, and house any visitor to your home for an indefinite period if they were in need of your assistance (can you imagine the revival of such a practice today? If only we still possessed a trust of our countrymen to rival this). A “suppliant,” or one in need of your help, would likely only wish to stay for a night or so, just long enough to recover from whatever misfortune first brought them to your door. This suppliant could also be Zeus himself in disguise, as he was the patron protector of the suppliant and protected them.

Well, it seems that Sisyphus had little regard for Zeus or what the law of hospitality demanded. When the day came for his mortal existence to end, Hades and Zeus had arranged a special torment for him in the Underworld; he was condemned to push a large boulder up the face of a mountain until he could heave it over the peak. In an act perhaps designed to curry the favor of Zeus, Hades enchanted the boulder so that just when Sisyphus had it teetering on the edge of the mountain top, he would lose his grip on it, and it would roll all the way back to the bottom. He would then have to begin again, forever doomed to lose his grip at the last moment. To this day, any task that seems interminable or frustratingly impossible to achieve can be referred to as “sisyphean.”

A horrible fate, is it not? So what is the key takeaway from this story that we can use to help guide us forward in our lives, one that helps us practice the cardinal virtues? It probably isn’t “if a suppliant knocks on your door, by all means let them in, bathe, and feed them!” Instead of pitying Sisyphus and being thankful that we aren’t him, we should, in one respect, work to emulate him. The act of “pushing the rock” itself, representative of seeking out challenges, is something we should always seek to do, once again following Arete’s path. This is phrased well by Jocko Willink, a former Navy SEAL turned author and business owner: “Getting the rock to the top of the mountain isn’t my goal. My goal is pushing the rock. If I ever got the rock to the top of the mountain and it stayed there…I’d push it back down myself. I want to struggle.” Without challenge or struggle, how can we possibly be expected to grow and improve? Marcus Aurelius captured this sentiment with this phrase: “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.” It is from engaging our challenges that we learn and advance. Without obstacles, how can we move forward? You can spend your life avoiding challenges for fear of failure, but it is through failure that we truly learn. If you take no risks, you remain at your current skill levels. To remain unchallenged is to remain unfulfilled. So, go find your next “rock” to push; it will draw out your courage and help to hone your temperance.

The final ancient narrative of the virtuous triad comes from Plato’s Republic. We know the story as the “Allegory of the Cave.” In brief, the story consists of a dialogue between Socrates and a young student of his named Glaucon. Socrates describes a scene for Glaucon to imagine: there are a number of “prisoners” kept chained in an underground cave where they have been all of their lives; they are unable to stand, move, or even turn their heads. Behind them is a “raised way,” or a wall, behind which is a path running parallel to it. All day long, walking along this path, are figures holding up objects on staves which extend up beyond the top of the wall. Behind this path is a roaring fire that generates light, casting the shadow of the objects carried by the figures on the path onto the one wall of the cave the prisoner’s can see. They debate the nature of the “objects” they see on the wall, unaware that they are but shadows. One day, a visitor discovers the cave and finds the prisoners chained there. He is horrified by their situation, and his sense of justice compels him to release one of the prisoners and lead him out into the world above so that his fallacious beliefs as to the nature of the world can be dispelled by a good dose of reality.

If you had spent your entire existence in a shadowy cave beneath the surface of the Earth, how might you react to being led out into the blazing light of the noonday sun? The liberated prisoner predictably collapses into a ball on the ground as his senses are unable to process everything they are forced to try and absorb. However, as time passes, he is able to lift his head as his eyes slowly acclimate to his new environment. The first thing to which the prisoner is drawn is to a pond of water in which he can see his own reflection–the closest thing to his old experience of everything he knew being but a shadow. Slowly, he looks about him to see a tree, then the landscape, the sky above him, and the sun itself. The questions begin flowing as he seeks to understand this brave new world to which he has been exposed.

The epiphany of learning of the world’s true nature not only motivates him to learn all he can about it, but also to return to the cave and share his discoveries with his comrades still shackled there. When he does so, they spurn and mock him, even threaten his life. “See what happens to anyone who dares leave us? He has come back down without his eyes!” The prisoners will not listen to his accounts, and refuse to accompany him back to the surface. They pity him and his delusionary state. In exasperation, he must leave them behind and return to the world as it really is, having tasted the world’s true nature, eager to learn more.

This story appeals powerfully to our search for wisdom and desire for justice. Each of us currently possess a worldview we hold as true. In the best case scenario, we would constantly be on the lookout for the perspectives and arguments that challenge our current beliefs, testing those beliefs against opposing views. If we are unable to reconcile our current beliefs with new knowledge, then the current beliefs must be modified to accommodate the superior positions. They simply must be. We can’t hold onto old, outdated, and demonstrably false beliefs just because changing them might be too painful for us.

The prisoners in the cave never even waver in their convictions that their “shadows” are the reality, and they refuse to listen to any viewpoints that contradict their worldview. The struggle the liberated prisoner undergoes could be defined as “cognitive dissonance,” the holding of two contradictory ideas in one’s mind simultaneously. In time, the prisoner’s old beliefs yield to the overwhelming evidence assailing his senses, and he renounces the false beliefs he once held.

Unfortunately, in the world beyond Plato’s hypothetical cave, the “prisoners” rarely succumb to the truth. In fact, even in the face of incontrovertible evidence, modern “prisoners” who refuse to even consider there just might be a different way to view the world that might be more akin to the truth dig in their heels and resist the open-mindedness that would allow them to learn and leave their caves of ignorance behind. The pain of cognitive dissonance and of the very real potential of being ostracized by friends and families who live in the same cave is too much to bear, accepting the truth just not being worth so high a price. All the same, those of us who value the quest for truth more than any shadow must continue to go back down into the caves, wherever they may be, and engage with the many prisoners who want nothing to do with the intellectual and spiritual freedom that comes with that quest. They prefer the tried and true shadows endorsed by their fellows.

Community can trump skepticism it seems. Despite their recalcitrance, we must continue to try, as they are our brothers and sisters in humanity with whom we must live, work, and strive to create the best civilization we can. Giving up on them simply isn’t an option, and falling prey to the narcissistic view that we have actually found the truth ourselves is also a danger. As Andre Gide once said: “Trust those who seek the truth, but doubt those who have found it.”

So, we must choose virtue over vice, look for rocks to push, and seek to dispel the shadows of ignorance from our own worldviews and the worldviews of others. The cardinal virtues have been valued and pursued for centuries, but understanding them is not enough. They must be practiced consistently, and that is more challenging than it sounds. In the end, the pleasure that comes from resisting a vice is far more satisfying than the fleeting sensation of indulging in it–and the vices abound, today more than ever before. We must set the example for those wandering aimlessly down Kakia’s path, refusing to seek rocks to push, or defending the validity of the shadows. Only when we willingly follow in Arete’s footsteps will true freedom and happiness find us.